I began writing this essay before any of the others I’ve posted here. This concept is what made me want to start this Substack in the first place. It is both deep and wide, and unexpectedly self-reflective. It has taken me six months to whittle it down to two parts (maybe three), which I hope are interesting to someone besides myself.

Before social media algorithms rotted everyone’s brains, before video games incited violent teenage behavior, before internet chat rooms became the corrupting forces of impressionable youth, there was another menace to society, and its name was television. When I was growing up in the early 90s, my sister and I were not allowed to watch television whenever we wanted. Most kids, I learned, would come home from school at 3pm and flip on MTV to watch Total Request Live. My parents refused to install cable until 2006, the year before I graduated high school.

The references kids made at school; Rugrats, MTV’s music videos, Comedy Central’s Daily Show, My So Called Life, Pete & Pete, and a dozen other widely popular shows among the preteen set went completely over my head. My first experience with cable coincided with that of my first sleepover at a friend’s house in elementary school. I don’t remember what we watched, only the expansiveness of the TV guide on loop, and the never-ending torrent of shows to choose from.

In those years I felt perpetually behind. Always asking what something meant or who a referenced character was. Slowing down everyone’s fun.

“Let’s play Rugrats,” someone said on a playdate.

“I don’t know how,” I told her.

“I’m Angelica,” she said. “You just pretend to be one of the babies.”

I was already a weird kid, and she gave up when I obviously didn’t understand what a Rugrat was, who Angelica was, their connection, or what being a baby had to do with anything. At the time, it seemed like everyone spoke the same shared language I hadn’t even known existed, never mind been taught.

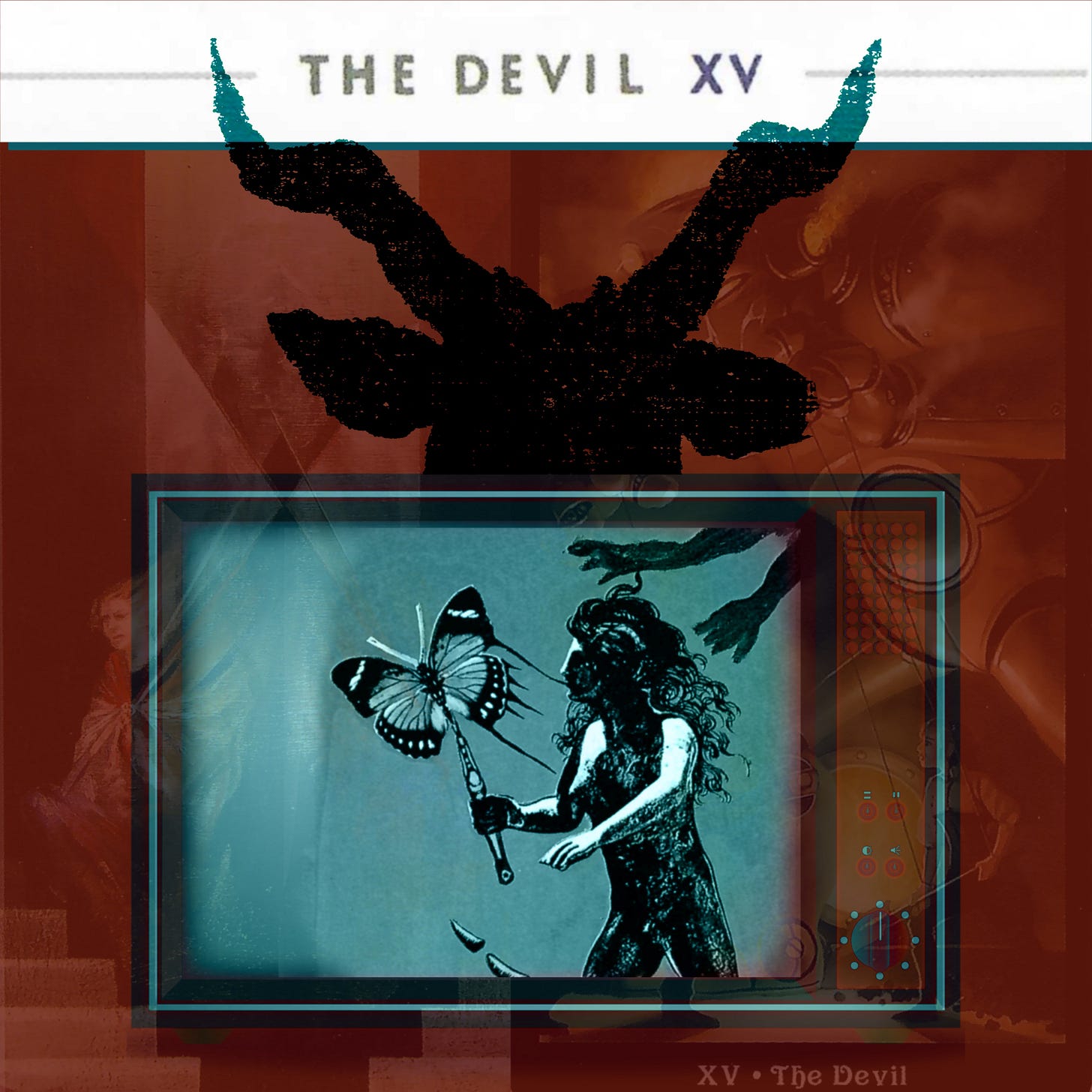

Television was vilified in my house, and by numerous anti-TV movements of the mid-to-late 20th century, which deemed television the culprit of some alleged fall of culture and democratic and/or polite society. In the views of mid-century activists like Jerry Mander and Neil Postman, television was determined to be the cause of the social ills that racked the 1960s, 70s, and 80s. I suppose if one looked at media and the technology that enables its consumption in their own vacuum, one could believe that.

Mander (who came up through advertising in the 1960s) and Postman, both would-be contemporaries of our fictional Don Draper, were born during the depression and grew up on radio in the 1930s and 40s. In 1938, when all were young children, American listeners fell into panic upon hearing Orson Welles’ The War of the Worlds broadcast, a moment now cemented in popular culture which led to public outcry against radio broadcasters, and calls for FCC regulation. Leading the charge of these angry parties was none other than the newspaper industry, who had been losing precious depression-era ad dollars to the shiny new medium of radio. Likewise, the rage against TV comes back in the end to advertising1.

Mad Men’s second season, set in 1962, coincides with the establishment of Harry Crane’s television department at Sterling Cooper. In 1962, TV was a newly important element of the American home. While the first season is mainly concerned with print and radio campaigns, which is how we’re given to understand agency founder Bert Cooper came up, Weiner’s second season opens with a television ad. Actually, it opens with the idea for a television ad based on a movie which is based on a stage musical which is loosely based on real events2. In one of the most effective storytelling mechanisms I’ve seen on TV, this one element, the distillation of a cultural touchpoint into a commercial tactic, establishes television as a central medium to the American lifestyle in the middle of the 20th century.

Harry Crane, who spent much of the first season talking out of both sides of his mouth to get ahead, works in the media department, and in The Benefactor (S2E3), stumbles into the realization that television, reaching this point of cultural relevance with no sign of slowing down, could be its own division. The character of Harry Crane is television personified; he’s unassuming, a bit squat and at first a carrier of the status quo who stumbles into his massive success. TV is getting big just as Harry is searching for his own value and largesse to the advertising industry, and he is, above all, an opportunist.

“Politics are in,” he tells the Belle Jolie Lipstick rep, trying to sell a sponsorship for a controversial episode of The Defenders, also titled The Benefactor and featuring the first televised storyline about the gray area of abortion’s criminalization and morality. Though Harry finds the subject matter to be upsetting, he demonstrates the earliest inclination to commoditize public opinions and rage-bait the American people that is so common on television (news) today. Harry’s duplicity is a character trait throughout Mad Men’s run, and follows much of the series in its exploration of duality. The Benefactor has the dual effect of overtly establishing Harry Crane’s value to Sterling Cooper, and subtly establishing television’s double-edged sword in American culture.

An historic television moment in its own right, The Benefactor can be looked at as a turning point; when TV truly became a medium of the masses, and not just an outlet for cultural propaganda created by some executives on Madison Avenue in the interest of some advertiser. Harry and the agency cannot sell the sponsorship, not just because it was a difficult sell in real life, but also to underscore the shift in advertising power, away from the agencies and towards the audiences TV was serving. If audiences wanted to watch something, advertisers were interested in getting their products in front of it. If audiences didn’t like what they were seeing, advertisers were less likely to want their budgets to be invested there. This still holds today.

Throughout Mad Men, Harry Crane remains our proxy for the medium of TV. We watch television grow in influence just as Harry’s influence grows in the agency. Neither television nor Harry are concerned by the ways in which they may offend or cause long-term damage to others; neither conceives of themselves as anything other than the pinnacle of greatness. Both are quietly absorbing the public’s time and attention, one buying; one selling. Harry Crane thus attains the linchpin status he’s been desiring, though both he and television would come to be regarded as a sort of necessary evil.

As the series progresses, TV continues to be used to both anchor the viewer in a timeline of real American events, the likes of which were broadcast widely for the first time in this era, and to reflect Sterling Cooper’s trajectory as a business3. The television is always on in Harry Crane’s office; he’s making sure all the ads run, because if they don’t, he’ll have to call the networks to demand make-goods for the client’s already-spent dollars, so they receive the number of ad units they paid for.

It’s on one of these afternoons of ad verification in Mad Men’s third season that the entire staff of Sterling Cooper stampedes into Harry’s office, where Walter Cronkite has just broken in to announce that John F. Kennedy has been shot in Dallas. The Grown Ups (S3E12) functions as the series’ all-important historical tipping point, and Harry Crane and his office television are its fulcrum, suddenly the most important duo at Sterling Cooper.

The Grown-Ups cuts between scenes via news bulletins from November 22 through November 25, 1963. The obvious appeal of television to advertisers had always been its mass reach, but this kind of shared tragedy, which was filmed and therefore could be broadcast out to the American people to experience as though they had been there for the next sixty (at least) years, had been unconsidered. There’s a school of thought that puts the beginning of “the sixties” on November 22, 1963; not just for its leading indication of civil unrest and a coming violent decade, but also as the moment when television media became the center of American history.

It’s likely that Kennedy’s assassination also marked the beginning of Mander’s and Postman’s theories that television is a devil, responsible for the downfall of society, when really, the civil inequities that had been building among a growing group of American people for decades had merely been made easily viewable for the first time, through TV.

I know for a fact that this is what my mother was raging against because she still rages against it, and that’s probably why I was so fascinated by advertising, but I won’t delve into my psychological complexes here.

We can argue about how closely a satire like Bye Bye Birdie is really mirroring Elvis Presley’s draft and deployment, but it serves my point here.

One of the last things the viewer sees on TV in Mad Men is 1969’s moon landing, a symbol of progress, futurism, and technological achievement that also parallels the agency’s successful sale to McCann Erickson, which catapults them into the big leagues.